Creating the space for listening

Creative activism as a way to start a conversation

Over the past few weeks I was lucky enough to attend a couple of online sessions run by Emily Kasriel, author of the book Deep Listening.

In Emily Kasriel’s framework, there are eight steps towards deep listening:

Create space

Listen to yourself first

Be present

Be curious

Hold the gaze

Hold the silence

Reflect back

Go deeper

A key learning for me was in the ‘reflect back’ stage – which as Kasriel emphasises, is not mindless repetition of the speaker’s own words, but a genuine attempt to ‘sift through the meaning and feelings behind what the speaker has said’. It is this, along with giving space for silence, that allows the conversation to go deeper. Perhaps counterintuitively, the asking of questions can stop the conversation from going deeper.

But I want to focus for now on the first step – creating space – which is something I’ve talked about before. This involves setting up an environment where the speaker/s feel comfortable and safe.

As I reflected on ways of creating space for listening, I thought back to my collaboration with the Center for Artistic Activism (C4AA) some years ago. These days I’m on the C4AA’s board, but I first encountered them during my time at the Open Society Foundations. Many of the groups we funded – working for the rights of people facing stigma and criminalization, or on quite specialised and technical issues like access to medicines – struggled to reach a wider audience beyond their own communities or small groups of dedicated supporters. As I was grappling with this challenge, I came across an article about the C4AA’s work and ended up funding and contracting them to offer training workshops bringing together artists and activists, to explore new ways of campaigning.

The C4AA’s workshops were a week long – three days of learning the theory and history of creative or artistic activism, and then two days to plan and implement a public action. A key activity on day 2 or 3 was experiencing a cultural event. A ‘cultural event’, by the Center’s definition, was not something tourists might visit, or an outing to an elite art gallery or a pricey show at the theatre. It meant, simply, something that was popular among local people. In Nairobi, it was dinner at an inexpensive roadside bbq joint. In Macedonia, it was an evening viewing Turkish soap operas. The assignment for the activists was to figure out why this thing was popular – what made people want to come, or watch, what made them feel at home, feel this was something for them. To look for the sorts of symbols, the colors, the rituals, that made it popular, that invited people in and made them want to stay. – and then figure out how to apply that to their own actions.

Insights from this exercise helped provide the workshop participants with creative ideas for the actions they went on to plan and carry out, over the space of 48 hours.

In Barcelona, this ended up as an impromptu carnival outside a major hospital, where the games were always rigged - providing a chance to talk to people about why their medicines were so expensive and how they could do something about it.

In Skopje it was the temporary establishment of a fictional utopian Macedonia in the main public park in the city, where passersby could come and bring their families, enjoy snacks and some music and learn about the importance of LGBTQI rights.

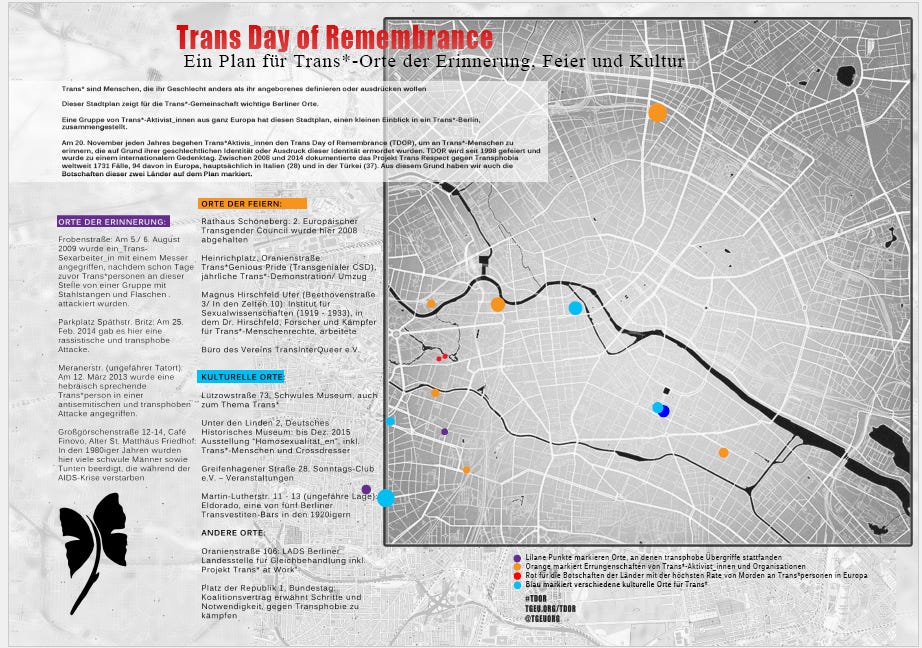

In Berlin it was a set of booths, inspired by the tradition of a ‘Stammtisch’, where people could learn juggling or origami from a member of Transgender Europe, and receive a map for Trans Day of Remembrance, marking memorial sites for the trans community across the city.

In Dublin it was a holiday booth in front of the statue of Molly Malone, with a peep show, chairs where people weary from Christmas shopping could take a break and get a hand massage from a sex worker dressed as an elf, take their ‘mug shot’ with Santa, and talk about why sex work is work.

In Cape Town, it was a booth on the seafront promenade, where sex workers offered joggers and walkers the opportunity to ask them anything.

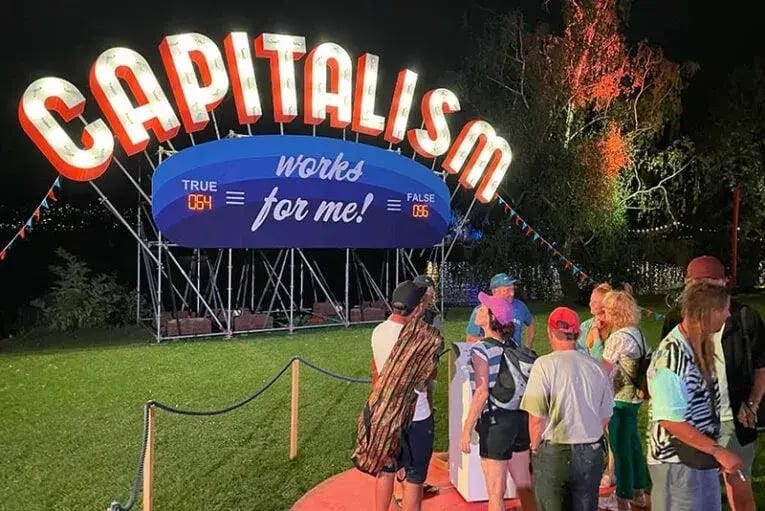

Steve Lambert, one of the co-founders of the C4AA, does something similar in his own artistic practice - such as his giant installation, Capitalism Works for Me, True/False.

To quote from the C4AA’s most recent newsletter: “People leaned in because the sign didn’t preach, it asked. It turned a red-flag word into a playful vote, sparking surprising conversations among strangers who would otherwise walk away.”

I doubt this kind of thing is what Emily Kasriel had in mind when she wrote about creating space for listening. On the surface, all of these examples are just stunts – disruptive, attention-grabbing public spectacles, motivated by advocacy and activism. But each represents an experiment with a fundamentally different approach from the common one of brandishing signs and shouting slogans. Each intervention aimed to create a warm, safe, fun, welcoming space, which people wanted to enter – providing not only the opportunity for activists to get their message across, but to start a conversation. To be listened to, and to listen in return, to hear people’s views, concerns and curiosities, and establish a relationship, however fleeting.

To me, another manifestation of listening as a political act.